Lean as a method works wonders to improve performance and serve customers. While limited as a philosophy, it gives a new pair of lenses to investigate operations. The core idea is to become more lean: how? by being fast and wasting little.

The featured picture is from the Toyota global website

Toyota was in the 70s and 80s by far the most successful manufacturer. Its Corolla range is one of the highest selling car models in history and it could not have been produced at scale and within budget if it weren’t for the Toyota production system. This system was the brainchild of Japanese excellence and American managerial theorists. It gifted us with cheap stylish cars with better production runs.

Reducing cycle time and reducing waste

Cycle time is the time to complete a process start to finish and is a rough measure of how fast you can deliver something. Think in terms of a hiring process: the back-and-forth of emails and internal checkpoints is actually one hour of focused work but takes weeks to complete. How can it be done faster?

By removing all that is not necessary for the process to deliver the final item, aka waste. Waste takes traditionally 8 forms (7 Japanese + 1 American):

- Transportation

- Inventory – don’t use it to hide problems!

- Motion (operations) – industrial engineers love removing this

- Waiting – especially cumbersome in large batches

- Over production

- Over processing (incl. rework) – like overdelivering

- Defects/Quality issues – do it right the first time!

- Skills – unused people potential

In its ideal implementation, lean makes you involve all the relevant stakeholders: this is necessary to perform a process analysis. Process analysis usually starts by:

- mapping all steps and finding

- the value adding steps (does the customer care about this?) and

- the necessary steps (will it fail if I don’t do this?)

Value Stream Mapping (VSM)

VSM is similar to process mapping yet with a larger scope. The idea: identify all the activities needed to deliver a product. Logically it requires four steps:

- define the product (or family of products sharing the same steps)

- Current state mapping – as it’s now being done

- Future state mapping – as we want it to be

- Action plan

The state map is often the bread-and-butter of consulting projects. It shows the high-profile overview of inputs, wait and process times, and the sequence of main tasks needed to get a job done. The usual slide looks often like this ugly duckling:

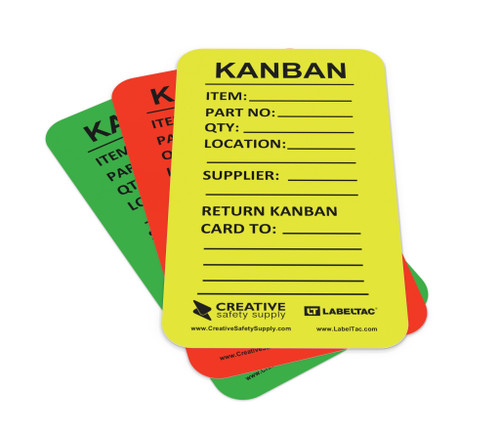

Kan Ban! – signal board – and Just in Time

The usual suspects for a future state mapping are the JIT and Kanban. JIT is a critical component of lean systems and cannot be simply pushed onto suppliers to reduce inventory.

JIT is an idea: can we work without lead times and overproduction? In lingo, can we minimize cycle time?

To do so, we have to work towards Single Minute Exchange of Dies (SMED) – fast moving from one process to another – and Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) – preventive maintenance -.

Moreover, two improvements are usually a good idea:

- Kan Ban is a visual production signaling system telling what-when-how much to produce: it limits the work in progress to a minimum. It allows to tag each item to a specific batch.

- Point of use storage (POUS) is the idea of storing inputs where you need them (thus eliminating the back-and-forth from a warehouse through dedicated space)

A Kan Ban is often a card with the information relative to a unit of production. It is – in essence – a way of organizing production so that you are only working on a specific item: I personally use a Kan Ban scheduling board to split tasks between to dos, doing, and verify (where the next action token is external).

Putting them all together these should reduce cycle time, and increase the quality. However, these tools have to work together in a lean system: being able to swap processes quickly (SMED) and reliably (TPM) is necessary to have low work-in-progress inventory (JIT) so that Kan Ban makes sense in a pull system.

A pull system is a system where downstream processes withdraw items from upstream processes, never delivering unless asked for. In other words, the action to be taken goes backwards: the customer asks for a bagel, the cashier books in the bagel, the kitchen gets the order. Pull systems have lower overproduction and motion compared to push systems: units are often delivered directly on the point of use (see POUS).

Poka Yoke! – error proofing

Preventing mistakes by making sure it is impossible to make a mistake: it is often the case for safety issues. Manhole covers may as well be round because any other shape would fall into the hole. It is an example of a failsafe design.

My favorite example is at the local gas station. The refueling process asks for 1) card 2) pump. This is way better than gas pumps that ask for pump number before processing the payment details and avoids delays in case the credit card gets rejected or the system cannot connect. All this can often be included in the big topic of choice design.

Beware of sub-optimization. Deming’s The new economics tells how we should try and focus the whole system, not the individual components. This is often the case when individual processes work at full capacity, which is not optimal system-wide as there may be more issues coming from the order of operations: this is also known as the theory of constraints.

KAIZEN! – good improvement

Kaizen means change for improvement. A process manager is responsible for not only the individual process improvements but also for the consequences on other processes connecting it to the final product (see how it all links with the process mapping part). When something is broken, the employee has the power to fix issues through kaikaku (radical change): these kaizen events are used to implement lean tools quickly especially in cross-functional teams.

Within the lean management idea, both the kaizen and the kaikaku are accompanied by:

- managerial buy in

- training for the employees

- visualization of the process and the results

Plan-Do-Check-Act – keep it on track

To keep the processes on track you need methods of involving managers and employees. Among these, the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) is one of the most famous. It latches onto other tools like the define-measure-analyze-improve-control (DMAIC) cycle.

Popularized by Deming (building on Shewhart’s cycle), the PDCA enables some discipline in process improvement. Planning is necessary to determine the scope (Ishikawa would say goals) of the cycle; the do part is the implementation of the planning stage, involving eventually the training of employees; check is an evaluation stage together with the documentation of the process (what worked, what didn’t, what is still to be done); the act part ensures the standardization of the practices in the check/study stage.

Wrapping up

In a nutshell, lean is a method of improving efficiency. It comes with the complete process mapping highlighting sources of waste and the current state of affair. It is meant to create a roadmap towards a future state of production.

It comes with its own (Japanese) terminology: a kan ban system of small, ear-tagged production batches, designed to poka yoke (avoid errors), and empowering employees to kaizen the production.

It all comes together when supported by management, trainings, and make the process visible (and accountable). To make sure the process is continuous and spot on, managers often use plan-do-check-act cycles.

I am preparing the Green Belt Six Sigma certification from Kennesaw State University. I am impressed by the production quality of the online materials and the simple, direct explanations in bite-sized servings. Highly recommended.

Most of my materials come from this excellent source.

Leave a comment